The Secret Sauce Behind PageRank Algorithm

1. Abstract

What happens when you search for a term on your browser? Google’s PageRank algorithm has revolutionized how the world accesses data on the web. The computation involved in ordering search results entails the indexing of trillions of pages and the creation of high dimensional structures to store and calculate different probabilities. This article provides a general overview of how the algorithm works by briefly exploring the general theory behind PageRank. In addition to explaining the mathematical foundations of PageRank, this article will present a simulation meant to help the reader gain some intuition of the stochastic nature of this algorithm. Also, it looks at some of the caveats including how PageRank deals with dangling links.

Random surfer on the web

2. Introduction

In the 1998 paper Bringing Order to the Web, Sergey Brin and Larry Page describe PageRank as a method for rating Web pages objectively and mechanically, effectively measuring the human interest and attention devoted to them. Simply put, the importance of a page can be thought of in terms of the probability that a random walk through the web will end up on a given webpage. This algorithm captures the global ranking of all web pages based on their location in the world wide web’s graph structure.

3. Theory

The underpinnings of PageRank are based on the hyperlink structure of different pages on the web. The links pointing to a page are considered as a recommendation from the page containing the outbound link. Inlinks from good pages (pages with a higher rank) carry more weight than those from less important pages. Each webpage is assigned an appropriate score which helps determine the importance and authority of the page. The importance of any page is increased by the number and quality of sites which link to it. The following equation represents the rank of any given page $P$:

$r(P) = \sum _ { Q \in B _ { P } } \frac { r ( Q ) } { | Q | }$where $B_P$ = all pages pointing to $P$ and $|Q|$ = number of outlinks from $Q$.

3.1 Computation

3.1.1 Markov model

Given x connected webpages, how would we rank them in order of importance? As mentioned earlier, this process constitutes a random walk on a graph representing different pages on the web. The walk’s position at any fixed time only depends on the last vertex (webpage) visited and not on the previous locations of the walk. Any time we are at a given node of the graph, we choose an edge (hyperlink) uniformly at random to determine the node to visit at the next step. This sequence maintains a transition matrix M whose columns contain the series of probability vectors $\vec { x } _ { 0 } , \vec { x } _ { 1 } , \vec { x } _ { 2 } , \dots$. The transition probabilities and the transition matrix for a random walk through this system are defined as:

$M _ { i j } = \left\{ \begin{array} { l l } { P \left( X _ { 1 } = j | X _ { 0 } = i \right) = 1 / \operatorname { link } ( i ) , } & { \text { if } i \vec { \sim } j } \\ { 0 , } & { \text { otherwise } } \end{array} \right.$Where $i \vec { \sim } j$ represents a directed edge from page i to page j and link$(i)$ represents the number of directed edges from i. The random surfer process can be visualized in a matrix containing probabilities that show the likelihoods of moving from one page to every other page. The matrix is row normalized with nonzero elements of row i corresponding to the outlinking pages of page i. The nonzero elements of column i correspond to the inlinking pages of page i.

$M = \left[ \begin{array} { c c c c c } { 0 } & { 0 } & { 1 / 2 } & { 0 } & { 1 / 2 } \\ { 0 } & { 0 } & { 1 } & { 0 } & { 0 } \\ { 1 / 4 } & { 1 / 4 } & { 0 } & { 1 / 4 } & { 1 / 4 } \\ { 0 } & { 0 } & { 1 / 2 } & { 0 } & { 1 / 2 } \\ { 0 } & { 0 } & { 0 } & { 0 } & { 1 } \end{array} \right]$These initial ranks are successively updated by adding up the weights of every page that link to them divided by the number of links emanating from the referring page. If a page has no outlinks, its rank is equally redistributed to the other pages in the graph. This redistribution is applied to all the pages in the graph until the ranks stabilize. Computing this distribution is the equivalent of taking the limiting distribution of the chain containing all the ranks.

3.1.2 Damping factor

In practice, the PageRank algorithm adds a damping factor $d$ at each stage to prevent pages with no outgoing links from affecting the PageRanks of pages connected to them. This heuristic relfects the probability that a random surfer on the web may choose to randomly “jump” from one node to another in the web graph. This may happen when he decides to type another page’s address directly into the search bar on the browser after hitting a dead end. The damping factor ranges from 0 - 1 where 0 corresponds to successive random jumps between different pages and 1 to a sequence of random successive clicks that inevitably lead to a page with no outgoing links. The sum of weighted PageRanks of all pages is multiplied by this value.

3.2 Simulating PageRank

In this section, R code that simulates PageRank is presented. It begins by generating a random n by n adjacency matrix containing the link structure between different pairs of pages in an arbitrary web system and proceeds as follows:

# Define function to generate an adjacency matrix

A_gen <- function (n, d) {

A <- matrix(sample(0:1, n*n, prob = c(1-d, d), replace = T), ncol = n, byrow = T)

return(A)

}

- The adjacency matrix generated above and the damping factor $d$ are used as inputs to the

page_rank()function defined below which calculates the ranks of all the vertices in the graph. The process starts with the initialization of a transition matrix and proceeds to iteratively calculate the rank of all pages until the Markov chain converges.

# Define PageRank function (p = probability of teleport)

PageRank <- function (A, p, output = T) {

# Define assertions

if (!is.matrix(A) | !all(A %in% 0:1)) {

stop(noquote('no (valid) adjacency matrix is provided.'))

} else if (!is.numeric(p) | p < 0 | p > 1) {

stop(noquote('p must be a probability between 0 and 1.'))

}

# Initialize transition matrix

s <- matrix(rep(NA, ncol(A)), ncol = ncol(A))

s[1, ] <- rep(1/ncol(A), ncol(A))

i <- 1

# Repeat Markov Chain until convergence

while (T) {

# Calculate transition vector at t + 1

t <- rep(NA, ncol(A))

for (j in 1:ncol(A)) {

t[j] <- ifelse(sum(A[j, ]) == 0

, 1 / ncol(A)

, p / ncol(A) + (1 - p) * sum(A[, j] * (s[i, ] / apply(A, 1, sum))))}

s <- rbind(s, t)

i <- i + 1

# Break if converged

if (i > 1) if (all(round(s[i - 1, ], 4) == round(s[i, ], 4))) break

}

# Build and return output

rank <- data.frame(as.character(1:ncol(s)), round(s[i, ], 4), rep(p, ncol(A)))

colnames(rank) <- c('Node', 'PageRank', 'P')

if (output) {

cat(noquote('PageRank Output:\n\n'))

print(rank[order(-rank$PageRank), c('Node', 'PageRank')], row.names = F)

cat(noquote(paste('\nPageRank converged in', i, 'iterations.')))

} else {

return(rank[order(-rank$PageRank), ])

}

}

# Generate graph

set.seed(327)

A <- A_gen(10, .6)

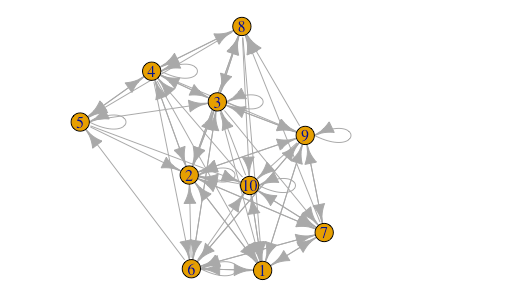

- The process modeled above is ran on a graph with 10 vertices and

r sum(A)edges. A visual representation of how different nodes in the graph are connected is also generated. Below it, is output showing the page ranks of all 10 nodes.

# Plot the graph

plot(graph.adjacency(A,'directed'))

# Run PageRank on example graph above with d = 0.2

PageRank(A, .2)

##

## Node: PageRank

## 2 0.1419

## 1 0.1143

## 3 0.1103

## 9 0.1078

## 10 0.1056

## 7 0.0995

## 6 0.0916

## 4 0.0904

## 8 0.0803

## 5 0.0582

3. Limitations

The original paper on PageRank by Brin et al (1998) presents dangling links on the web as a pertinent issue affecting the model. It decribes them as links that point to pages with no outgoing links and states that they affect the model because it is not clear where their weights should be distributed. The ultimate proposition made in the paper is the removal of all these links until all the PageRanks are calculated. Brin and Page postulate that the addition of these links thereafter doesn’t affect things significantly.

4. Conclusion

PageRank is a powerful tool that has greatly simplified and democratized the access to information on the web. The advent of this algorithm has seen the emergence of a Search Engine Optimization industry which is a discipline focused on organically increasing the reputation of online content to increase visibility and improve rankings on the web. However, one of the major challenges this poses to PageRank is that commercial entities may try to artificially game the system to increase the visibility of their online content.

5. References

-

Langville, Amy N., and Carl D. Meyer. “The Mathematics of Google’s PageRank.” Google’s PageRank and Beyond: The Science of Search Engine Rankings, Princeton University Press, 2006, pp. 31–46. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt7t8z9.7.

-

Benincasa, Catherine & Calden, Adena & Hanlon, Emily & Kindzerske, Matthew & Law, Kody & Lam, Eddery & Rhoades, John & Roy, Ishani & Satz, Michael & Valentine, Eric & Whitaker, N. (2018). Page Rank Algorithm.

-

Dobrow, R. P.. Probability : With Applications and R, John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated, 2013. ProQuest Ebook Central, https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/amherst/detail.action?docID=1449975.

-

Sergey Brin, and Larry Page. Bringing Order to the Web.

-

Hwai-Hui Fu, et al. “APPLIED STOCHASTIC MODELS IN BUSINESS AND INDUSTRY.” Damping Factor in Google Page Ranking, 29 June 2006, pp. 1–14.